Nearly all our day-to-day decisions, actions and challenges can be described by some economic theory; but the subject of economics remains largely esoteric. While undertaking graduate studies at Columbia University in the city of New York, the study of economics gave me sleepless nights as I suspect it has many scholars before me. I stayed awake analyzing the situation in Africa today and the more I learnt the more I realized that although there isn't one single thing I can do to save the situation, there may be a couple of things I can do and one of them is to share with you my analysis of why our continent may be chained to an unachievable dream of economic development or at least an unrealistic path to the said development.

I come from a family of revolutionaries. Right from a great great grandfather King Ndagara, the last king of Buhwejhu who died fighting the colonialists. My family tree is scattered with dead heroes. People who saw right and wrong and no in between, people who shook establishments and went against status quo hoping to make a positive change for others in spite of the imminent losses to themselves. The revolutionary in me awakens more with every book I read. Sharing knowledge, ideas and the unanswered questions of my sleepless nights in New York, will if nothing else, help me understand this world better.

Foreign Aid

Official development assistance (ODA) is one form of foreign aid. There are several forms of foreign aid – grants, loans and humanitarian aid; we could even choose to call preferential trade agreements that developed countries extend to developing countries a form of aid. But Official Development Assistance (ODA) specifically refers to grants and loans and it will define the scope of foreign aid in this piece.

Foreign aid usually refers to a transfer of income from one country to another. It is meant to benefit both the recipient and the donor country even though the latter intention is not usually expressed. The recipient's interests are mostly economic growth and development while those of the donor are typically financial and/or political.

Financial gains are accrued by producers in the donor country if the recipient country buys donor exports using aid dollars or if consultants are hired from the donor country to provide "technical assistance" on aid-funded projects. Political gains for the donor are illustrated best by the case of African former French colonies in which France used aid for political support – countries received aid only under the explicit agreement that France would be consulted before these African countries voted on any important issue at the United Nations. The US also gave aid to Spain on the terms that it could build military bases on their soil.

The donors design the machinery that implements the transfer of aid. This gives the donor leverage or the ability to use aid to bring about the recipient's compliance with any action that's in the donor's interest. Limiting the analysis to financial interests, the donor is most likely to set up the machinery in order to ensure that the recipient country imports its goods and services. This is usually done subtly but can also be done explicitly in form of set conditions, as is with the case with "procurement tying" which clearly specifies where all the materials and equipment used in aid funded projects must be imported from. It's anybody's guess where that might be.

There is a strange theory in economics called the transfer paradox, which postulates that a transfer of income may worsen the recipient's terms of trade while improving the donor's terms of trade if the recipient has a higher propensity to spend on its export good than the donor. English translation: A transfer may cause the donor's export prices to rise relative to its import prices and the recipient's export prices to fall relative to its import prices leaving the recipient worse off and the donor better off after the transfer.

This theory was stumbled upon when, after World War II, France demanded war reparations payments from Germany (payments to compensate for France's loss during the long war against German invaders). The effect of the payments on either country sparked a historic argument between two great economists, John Keynes and Hecksher Ohlin. Keynes argued that Germany would have to decrease its export prices on top of paying the war reparations and would therefore suffer greatly but Ohlin argued that Germany would not necessarily have to worsen its terms of trade. Eventually, the reparations were never paid out but the theory of the "transfer paradox" was born. It explains a situation that arises when a transfer of income leaves the recipient country worse off and the donor country better off. Interestingly, when a recipient country uses all of its aid dollars on imports from the donor, the transfer is "a fully effected transfer". On the other hand, when the recipient country spends only a small portion of the aid on imports from the donor and the rest on local goods, the transfer is "an under-effected transfer". Note the subtle implication of the semantics!

Clearly, a fully effected transfer could lead to a case of the transfer paradox – decreasing welfare of the recipient country and improving that of the donor. But interestingly, the IMF is very persistent in encouraging "full aid absorption" which in English means spending aid on imports. So is the IMF misleading poor African countries? A good hypothesis for research would be: under what conditions is a country most susceptible to the transfer paradox phenomenon when there is full absorption of aid as recommended by the IMF? But even without complicated and rigorous statistical analysis, I believe our policy makers – legislators, ministers, politicians should be aware of these ambiguities when dealing with aid issues.

The contradictions of foreign aid are not a favorite subject for many but books like "Confessions Of An Economic Hit man" give a chilling account of how foreign aid has long been used, along with other more vicious and even bloody tools, by the US government for purposes of "empire building". And if that is too conspiratorial for your reading appetite, there is the argument between two renowned economists – Jeffrey Sachs and William Easterly that echoes that of Keynes Vs Ohlin. It is spelt out in two books – " The end of poverty" by Jeffrey Sachs and "The White Man's Burden" by William Easterly. Jeffery Sachs is a strong proponent of aid for development while Easterly thinks aid has failed to work in the past for various reasons and there is no reason it will work now as long as proponents of aid do not address the old reasons for failure of aid to promote growth and development for recipient countries.

All the ado notwithstanding, the world's richest countries announced a $50 billion increase in aid at a G-8 meeting in July 2005 mainly aimed at meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) articulated under the auspices of the United Nations. Now is definitely the time to investigate the many contradictions of foreign aid because like it or not, the money is on its way!

My people have a saying "Mira; mir'omuriro, chweera; chweera obunuzi" (If you swallow that which is now in your mouth, it will burn your throat like a fire and yet if you spit it out, you will lose out on so much sweetness).

During my sleepless nights, when I am not thinking about the enormous bills that come with living in New York, I find myself wondering what my great-great grandfather King would have done as a leader. In the light of these contradictions, would he have performed a crude cost benefit analysis and accepted the aid if the benefits outweighed the costs or would have rejected foreign aid outright - based on principle? I am more inclined to believe that he would choose the latter but of course I will never know.

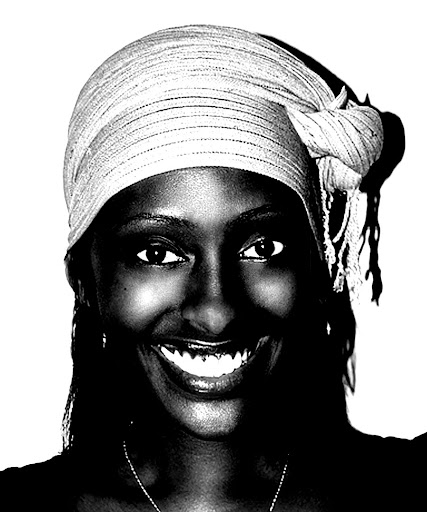

Olivia Byanyima.